While the

Siege of Otrār was in progress Chingis Khan and his youngest son Tolui led the main Mongol army southwest to Bukhara. With them were Turkish auxiliaries who by then had sided with Chingis. “These fearless Turks,” according to the Persian historian Juvaini, “knew not clean from unclean [i.e., were not Muslims], and considered the bowl of war to be a basin of rich soup, and a held a mouthful of sword to be a beaker of wine.” No mention is made in any of the sources about crossing the Syr Darya, usually a intimidating operation, which leads the Russian Orientalist Barthold to opine that the river was frozen over by the time the Mongol army reached it and that they crossed over on the ice. This could have occurred no earlier than late November or early December. The first major town the Mongols encountered south of the Syr Darya was Zarnuq. “When the king of planets raised his banner on the eastern horizon [at sunrise, to the more prosaic-minded],” Chingis and his army appeared before the city walls, according to Juvaini. The inhabitants retired into the Citadel, closed the gates, and at first were determined to resist the Mongol attack. A man named Danishmand (

danishman means “consultant”), either a commander of one of the Turkish auxiliary units or a Khorezmian trader who had attached himself Chingis’s army, was sent into the city to talk some sense into the local panjandrums. After they threatened him with bodily harm, he shouted at them:

I am . . . a Moslem and a son of a Moslem. Seeking God’s pleasure I am come on an embassy to you, at the inflexible command of Chingiz-Khan, to draw you out of the whirlpool of of destruction and the trough of blood . . . If you are incited to resist in any way, in an hour’s time your citadel will be level ground and the plain a sea of blood. But if you listen to advice and exhortation with the ear of intelligence and consideration and become submissive and obedient to his command, your lives and property will remain in the stronghold of security.

After this verbal onslaught the local dignitaries thought it wise to surrender. But they insisted that Danishmand be held hostage while they negotiated terms with Chingis. If any of them were harmed it would mean Danishmand’s head. First they sent forth a delegation of factotums with gifts for the Mongol potentate. Chingis did not appreciate this gesture. He dispatched a message to the city fathers telling them to quit wasting time and to appear in person before him immediately. Receiving this summons “a tremor of horror appeared on the limbs of these people” and they presented themselves to Chingis forthwith. Without further ado he accepted their surrender and then ordered all the inhabitants to vacate the city. During a headcount young men were singled out and drafted as levies for siege work in the anticipated attack against Bukhara. Then while the people of Zarnuq were encamped on the the plains outside the city the citadel was leveled. Juvaini does not specifically say the abandoned city was looted, but presumably it was. Still, the inhabitants had escaped with their lives and whatever personal possessions they had managed to keep out the hand of the Mongols. After the invaders left the they were free to return to what remained of their city. The relatively benign fate of Zarnuq led Chingis’s soldiers, perhaps Turkish auxiliaries, since the words are Turkish, to nickname the town Qutlugh-Baligh (“Fortunate” or “Blessed” Town).

To reach Bukhara from Zarnuq the Mongols now had to cross a fearsome stretch of the mostly waterless Kyzyl Kum Desert. Normally this would have been a daunting if not impossible march for a large army, but a Turkmen caravan boss in Zarnuq, apparently with a grudge of his own against the Khwarezmshah or perhaps in return for coin of the realm, showed Chingis a secret road from Zarnuq to Nur, the first city south of the desert. After crossing 150 or so miles of desert the Mongol army skirted around the western end of 100-mile long Lake Aidarkul and proceeded another twenty-five miles to Nur. Henceforth the route from Zarnuq to Nur directly across the desert became known as the Khan’s Road (Juvaini tells us that he himself traveled this road years later, in 1251). Again the belief of the Khwarezmshah’s advisors that his army would have an advantage over the Mongols because of their knowledge of local roads and terrain proved false. At least some elements of the local populace were proving to be more than willing to assist the invading Mongols.

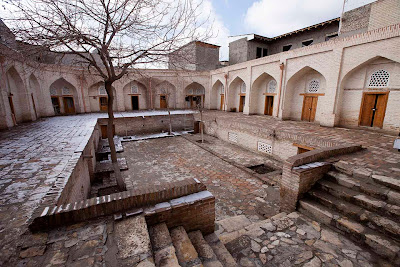

The ancient city of Nur (now Nurata), 210 miles southwest of Otrar, had long served as a strategic outpost on the northern borders of Mawarannahr, a gateway between the nomad-dominated deserts and steppe to the north and the cultivated lands of the Zerafshan River basin to the south. Alexander the Great had arrived here in 327 b.c. and either built or enlarged and strengthened an already existing citadel on a hilltop on the edge of the city, apparently hoping to use the area as a base for further advances into Mawarannahr. Ruins of Alexander the Great’s fortress in current-day Nurata (click on photos for enlargements)

Ruins of Alexander the Great’s fortress in current-day Nurata

Current-day Nurata from the ruins of Alexander the Great’s fortress

His men also built a network of underground water pipes, parts of which remain in use down to the present today. One of Alexander’s generals died here and was buried near the base of the citadel, where his tomb can still be seen. Tomb of Alexander the Great’s General

The town was also famous for its prodigious chasma, or spring, at the base of the citadel. According to legend the spring was created when the Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali struck the ground with this staff and water gushed forth. This story is no doubt apocryphal, but the spring—apparently because of its alleged association with family of the Prophet, would by the tenth-century become an important pilgrimage site. Writing in the 940s, the Samanid historian al-Narshakhi, noted: Nur is a large place with a grand mosque. It has many ribats [caravanserais]. Every year the people of Bukhara and other places go there in pilgrimages. The person who goes on the pilgrimage to Nur has the same distinction as having performed the pilgrimage [to Mecca] . . . many of the followers of the Prophet are buried there (May God be pleased with them until the day of Judgement).

The Chasma at Nurata

A Mongol commander by the name of Dayir led the Mongol vanguard to Nur. On the outskirts of town they halted in some groves of fruit trees—now barren, as it was January—and camped. That night they cut down trees and used the wood to fashion scaling ladders. The next morning they rode up the city walls holding the scaling ladders in front of them The sudden appearance of this Mongol vanguard via a route thought to be known only to merchants caused the watchmen on the walls to mistake it at first for a trading caravan. As the horsemen got closer the watchmen saw the ladders and realized that the mounted men were invaders. The gates of the city wall were thrown shut and the city fathers commenced debating among themselves what course of action to take. After much argument it was decided that they had no choice but to throw in the towel. In Juvaini’s account of the city’s fall no mention is made of the citadel built or upgraded by Alexander the Great. Either it was not longer an active fortification by the thirteenth century or the local panjandrums decided it could not be defended.

An envoy was sent to Chingis Khan, who was still advancing across the desert with the bulk of his army. Accepting the city’s surrender, he ordering the city fathers to submit to his general Sübetei, who had already arrived at Nur in the wake of the vanguard. Sübetei herded the inhabitants out of town, allowing them to take along only “what was necessary for their livelihood and the pursuit of husbandry and agriculture, such as sheep and cows . . .” He further ordered that “they should go out on to the plain leaving their houses exactly as they were so that they might be looted by the army.” In return for this acquiescence the Mongols agreed not to inflict bodily harm on anyone.

When Chingis Khan finally arrived in town he ordered the city’s inhabitants to cough up 1500 dinars, the same amount they paid in taxes to the Khorezmshah each year. Half of this sum, we are told, was paid in women’s earrings. The fact that the locals still had dinars to pay, and women earrings to hand over, would seem to indicate that individuals had not been robbed at least of the possessions on their persons, even though the town itself had been sacked and looted. As usual, young men were dragooned as levies, although according to Juvaini only sixty were taken. Compared with the devastation the Mongols would later inflict on cities which resisted them, Nur, like Zarnuq, got off rather lightly, even if the women did bemoan the loss of their earrings. Both cities were essentially sideshows. The big prize was Bukhara, eighty-five miles to the southwest.

From Nur the Mongol army rode fifteen miles south-southwest through desert-steppe to a 2641-foot high pass, a thousand feet higher than Nur itself, through the Karatau Mountains, themselves part of the Aqtau Range, east-west trending mountains with peaks of up to 5,485 feet. Looking north from the 2641-foot pass towards Nurata

To the northeast loomed the snow-covered flanks of the Nuratau Range, with peaks of up to 7116 feet. After crossing the pass they descended onto a strip of grassy steppe where the Mongol horses must have felt right at home. Even if the steppe was covered with snow in late January or early February the sturdy mounts would have had little trouble pawing down to the dry grass, which they must have craved after passing through the bleak Kyzyl Kum Desert. Steppe between the 2641-foot pass and the Zerafshan River. The Mongol horses must have thought they were at home in Mongolia.

Fifteen miles from the pass miles Chingis Khan and his army finally reached the cultivated lands along the fabled Zarafshan River. The valley of the river had hosted settlements, towns, and cities (a sedentary societies) for over 3000 years and it had always been the main populous region of Mawarannahr, with the two main cities of Bukhara and Samarkand alternating as the capitals of a long procession of fiefdoms, kingdoms, and empires. The Greeks of the third century b.c. called the river Polytimetus. Also known as the Sughd, or Sogd, River, its lower valley later became the heart of the old Sogdian realm. The current name of Zarafshan comes from the Persian zar-afshān, meaning "the sprayer of gold"), a reference to the gold-bearing sands and gravels found in the upper reaches of the river.

The Zerafshan begins at the Zarafshan Glacier on the Koksu Mountains, themselves outliers of the Pamirs. From its source at an elevation of about 9200 feet the river flows west for about 180 miles, flanked on either side by the Turkestan and Zarafshan mountain ranges. Just below the ancient city of Panjikent the river debouches out onto the plains of Mawarannahr and twenty miles farther on passes by Samarkand. From here it flows about 115 miles east-northwest before turning to the south-southwest and flowing through the Bukhara Oasis. In pre-historic times the river probably drained into the Amu Darya River, but even by the time of Alexander the Great in the third century b.c. it was already petering out in the sands of the Kyzyl Kum Desert southwest of Bukhara.

The Zerafshan River

Crossing the no doubt frozen river the Mongols emerged on the Royal Road, the main caravan thoroughfare between Bukhara and Samarkand. Probably the first town they encountered was Karminiya (current-day Karmana), forty-five miles to the northeast of Bukhara. Known during Sogdian times as Badiya-i-Khurdak (“little pitcher”), the town got its new name from eighth-century Arab invaders who because of the water and soil in the area called it ka-Arminiya, or “similar to Armenia”. Karminiya had been heavily damaged by the Khorezmshah Arslan during his war against the Qara Khitai in mid-twelfth century and apparently did not figure as an important city by the time Chingis Khan arrived on the scene. The mausoleum of Mir Sayyid Barham, built in the late eleventh century during the rule of either the Qarakhanids or Seljuks, is probably the only building in the town to have survived from the pre-Mongol days down to the present.

The mausoleum of Mir Sayyid Barham

About ten miles past the river, where the ancient caravan route swung back out into desert steppe, they might well have passed the famous Rabat-i-Malik, a huge caravanserai built by the Qarakhanid Khan Shams-al-Mulk Nasr (r. 1068–1080). Its 40-foot high portal with elaborate brickwork decoration and enormous walled courtyard signaled that the Mongols were now on the main trunk of the Silk Road, the ancient trade corridor between the Orient and the Occident. The surviving portal and ruins of the caravanserai can still be seen beside the modern highway between Bukhara and Samarkand. Entrance to Rabat-i-Malik Caravanserai

Nearby was a huge well of sweet water which would have slaked the thirst of the men and their horses (the brick dome which now covers the well was not added until the 14th century). Entrance and Dome of the well at Rabat-i-Malik Caravanserai

After riding another fifteen miles east-southeast the Mongol army finally reached the edge of the greater Bukhara oasis, a forty mile-wide and fifty mile-long swath of cultivated land which in addition to Bukhara itself was home to dozens of small cities, towns, and villages. Bukhara Oasis

They probably saw the wall known as “Kanpirak”, measuring over 150 miles in length, which had once surrounded the entire Bukhara Oasis. Kanpirak is supposedly an archaic term for “old woman”, which would at first glance seem an inappropriate term for a wall. One local historian points out, however, that the term “old virgin” might be a more accurate translation, in which case it might connote that the wall was thought to be impenetrable. In any case, the wall was probably built in the fifth or sixth century a.d. Between the years 782 and 830 it was repaired and upgraded as a bulwark against the continuing incursions of nomadic peoples from the north. Maintaining the lengthy wall was an immensely expensive undertaking, however, and required enormous outlays of man-power. At the beginning of the Samanid era in the ninth century Amir Ismael famously declared, “While I live, I am the wall of the district of Bukhara,” implying that he would guarantee the safely of the area by force of arms and that expensive walls were no longer needed. The Kanpirak was henceforth abandoned, and by the time the Mongols arrived it may have been in ruins. In any case, neither Juvaini nor any other Persian historian mentions the wall and it proved no obstacle whatsoever to the Mongol invaders.

The first settlement inside the wall was the town of Tawais. Formerly known as Arqud, in Persian, or Kut, in Turkish, meaning roughly “fortunate”. Arab invaders renamed it Tawais (“Endowed with Peacocks”) in 710 because it was here they saw their first peacocks—not a native bird of Arabia—in the gardens of the town’s prominent citizens. The town had been well-fortified, but by the time Chingis arrived the local fortress had fallen to ruins, already destroyed in earlier fighting between the various contestants for the Bukhara conurbation. The town was formerly famous of its Zoroastrian temple, although presumably it had disappeared by the thirteenth century, by which time it boasted of a large Friday mosque. Tawais was also famous for its great trade fair, which was held very autumn and lasted for seven to ten days. Merchants from all of Mawarannahr and the Ferghana Valley attended this fair, which operated under one unusual condition: no item bought could be returned, even if it was later proven that the seller had engaged in illegal trickery and deception. Although probably in a hurry to get to Bukhara, presumably the Mongols took time to engage in at least a cursory looting of the town and to dragoon levies for the anticipated lengthy siege of Bukhara. Today Tawais remains as the small village of Tavois, close by the modern town of Kizil Tepe. Now, as in the thirteenth century, it marks the place where the cultivated land of the Bukhara Oasis abruptly ends and the desert steppe begins.

The village of Tavois

Fifteen miles east of Tawais was the town of Vabkent, The Mongols may have homed in on the town’s minaret, visible for miles around on the flat Bukhara Oasis. Commissioned by Abd al-Aziz II, a member of a powerful Bukhara family during the time of the Qara Khitai Khanate (c. 1125–1218), the 127-foot high minaret, completed in 1198–1199, was the second highest in Mawarannahr, after the Kalon Minaret in Bukhara itself, and served as a beacon for caravans and travelers approaching from the north. The Mongols left it unharmed, and it stands to this day, although the mosque it was once attached to has long since disappeared.Minaret in Vabkent

The eighteen miles from Vabkent to Bukhara was an almost solid procession of towns, villages, gardens, and orchards. Among the more prominent towns were Shargh and Iskijkath (no longer existing under these names) on either side of one of the canals feeding off the Zerafshan River. In the twelfth-century Sultan Arslan, the grandfather of the Khorezmshah ruling at the time of the Mongol invasion, had built a substantial bridge made of burnt brick across the canal connecting the two towns. Both were important trading centers; Iskijkath had a trade fair every Thursday and Shargh every Sunday. An important local trader built a big Friday mosque in Iskijkath, but after imams in Bukhara complained that it was attracting their flocks only one service was ever held in it. No mention is made in the various accounts of the plundering outside of the city of Bukhara, and perhaps the Mongols in their hurry to reach Bukhara hurried on through them, but it is hard to imagine that sometime during their stay in the area these rich market towns were not subject to looting and plunder.

Not long after passing through these towns yet another minaret loomed on the horizon. This was the 155-foot high Kalon Minaret in the heart of Bukhara, the tallest in Mawarannahr. Its appearance signaled to the Mongols that the long-sought after goal of Bukhara was now within their reach. By early February, 1220, Chingis Khan, his son Tolui, and the Mongol army arrived on the outskirts of

Bukhoro-i-Sharif—Holy Bukhara.

Kalon Minaret in Bukhoro-i-Sharif